Story by Ian Baker

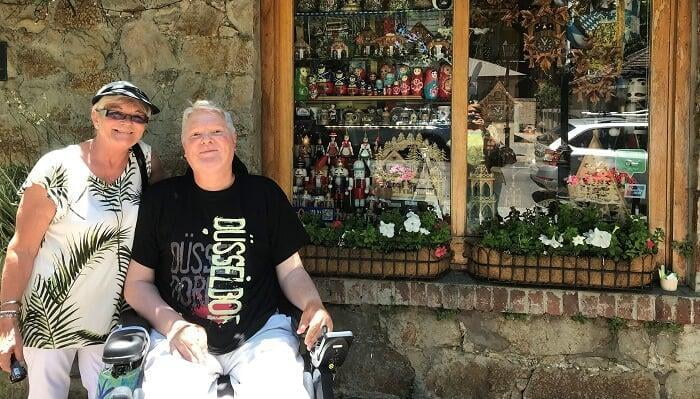

Sharon Brill found herself drawn to disability support work for its variety and autonomy … and for the deep partnerships she formed with clients such as Greg Grigarius.

In the second week of March 2020, about five days before the Australian Government mandated a two-week quarantine for arrivals from overseas, Sharon Brill returned from a holiday in Egypt to her home on the Mornington Peninsula. Aware that she might have been exposed to coronavirus, she applied for two weeks’ sick leave from AQA and stayed home.

She was approaching the time of life at which people were deemed exceptionally vulnerable to COVID-19. She wondered whether it was time to retire from the disability support work that had rewarded her for the past dozen years.

“I would never have forgiven myself if I infected one of my clients,” Sharon reflects.

“And with my age, I was very wary.

“But then I got very confident. “I thought: I have been nursing for 45 years and I know what to do.

“I knew that if I took proper precautions I would not be infected.”

A long-term client, Greg Grigarius, says: “Sharon will go the extra mile.” He counts himself lucky to have been the second client she took on for AQA.

“Sharon is a very good support worker with a high work ethic,” Greg says. “Carers can learn from her energy and skill set. She thinks one step ahead – she just knows, and that’s experience.”

Just too much

Sharon grew up on a farm in New South Wales, was driving a tractor at 10, began nursing at 17, and completed her training at a little private hospital, as she describes it, in South Australia. “It was fantastic,” she recalls of that education.

She nursed in hospitals, married, and had two children. After 10 years her marriage ended, and she switched to nursing in residential care facilities for the elderly.

One of her sisters, a psychologist, asked whether Sharon could look after a woman who needed care at her own home. Sharon said she would give it a try.

“I joined AQA so I could attend to this lady, who lived out here,” she recalls. “She was very different to Greg – very demanding. But we got around that, and we ended up being really good mates.”

After her first client died, Sharon began working with Greg. Other clients were offered. She was still working at a nursing home four nights a week.

“I thought, this is just too much,” Sharon remembers. “I had to make a decision whether to go fully with one or the other. I wasn’t enjoying my night job that much, and so I knew what I was going to do.”

More of a life

Among the many elements of support work that Sharon enjoys is the autonomy it affords her. She can build relationships that reward her competence.

“In a nursing home, you’re working with other staff and you’ve gotta work with them all the time,” she observes. “This is so different.

“You have your own space. You don’t have any bosses over your head. You haven’t got anyone driving you or pushing you. It’s what you make it and how you make it.

“It’s more of a life than just going to work in a hospital and staying there till your shift finishes. I’m getting out and about doing things, and doing all different sorts of jobs for people. It’s different every day.”

‘You don’t have bosses over your head.’

Part of the household

Sharon says she treads lightly for about 12 months with every new client. It takes that long, she says, to understand what the client needs from her, and for the client to understand her.

“When I’m going into a new client’s home, I feel a bit like I am an intruder,” she says.

“This is a private area, and you have to be very wary about where you tread in that sort of area.

“I let the client know who I am. I let them know that I’ve nursed all my life, and that sort of thing. But I’m cautious about what I’m doing and how I’m doing it.

“Until you get to know the client, and then you talk with them like you’re old friends.”

Greg appreciates that unassuming approach.

“It takes a while for people to feel comfortable,” he notes. “Also, for someone to know where stuff is in your house.

“And for me, identifying the individual’s personality traits.

“Can I make a joke? Will their political views differ from mine? So, you as a client are a bit wary as well. The synergy has to be there.

“It’s not only the disabled person who has to be considered; it’s also the partner and the rest of the family. I’ve had my kids say, ‘That support worker wasn’t very pleasant.’

“But Sharon is like an auntie. She’s seen my daughters from young children to grown women. When someone comes into your home for that many years, you develop a bond. They become part of the fabric of the household.”

‘Sharon is like an auntie. She’s seen my daughters from young children to grown women.’

The meaning of life

Greg met his wife, Karen, at a clinic he had attended to have his heart tested. One of his brothers had died recently from heart failure. Greg knew that he too was at risk, because he too had muscular dystrophy, a hereditary disease that had slowly weakened his muscles and for which no cure had been found.

Diagnosed at 13, Greg was 31 when he walked unsteadily into Karen’s consulting room.

“We just connected,” Greg says. “After the appointment I thought: nice lady. But I hadn’t thought it appropriate to ask her out.”

That day had been Karen’s birthday. On a call with her grandmother, she spoke of Greg and received some advice. She contacted Greg and informed him that he had left behind some keys.

“Which I hadn’t,” Greg says.

“Karen is a bit of a deep thinker. We had been chatting at the appointment. I had been engaged for three years but it hadn’t panned out. I wasn’t looking for another partner. I had been asking myself what was the meaning of life, and had been reading about spirituality. So I was looking for something a bit deeper.

“Karen had studied theology, and so we had started talking about spirituality and religion. For Karen, the physical body is a shell. She saw my spirit.”

Making a difference

For five years after he married Karen, Greg did not need assistance from carers, even though he lost the strength that he needed for walking. But his dependence on Karen was growing.

“We wanted to avoid that,” he says. “Karen is a professional, and she wanted to be a professional. And I didn’t want to marry a carer; I wanted a life partner.

“Having support workers made a big difference to our lives. It allowed Karen to have her independence, and it allowed me to have my independence.

“To have your wife as your carer, it takes away from the intimacy of the relationship. Some partners walk away because it becomes too much. Karen and I had young children, and we wanted to stay as a family.

“I was working in those first years of our marriage. I think Karen didn’t realise at the time how bad it would get. About a decade later that took a toll. She had some doubts, like any marriage has doubts. But we worked through them.”

‘We get involved in things. We like the theatre. We like all varieties of music.’

A normal life

For much of his career Greg was a Federal public servant, managing cases for Centrelink. In his 40s he took a job in the private sector, as an account manager for an energy company. At the age of 45, the cardiomyopathy arose that Karen had tested him for. Surgeons corrected it with a pacemaker, but Greg and Karen believed they could see what was coming.

“Karen said ‘Look, Greg, you probably won’t live five years,'” Greg recalls. “She said: ‘I’ll be the breadwinner; you retire.’ I became a Mr Mum, so that I was here for my kids when they got home from school.”

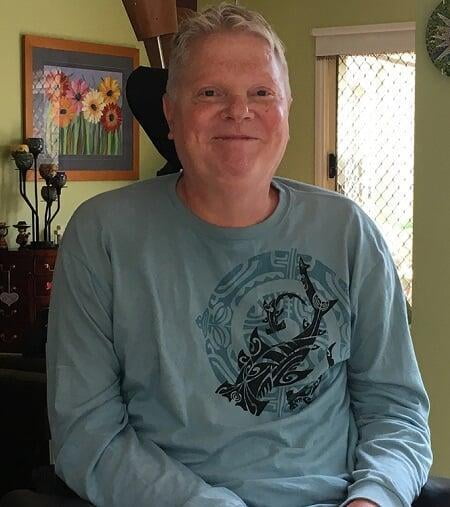

Thirteen years later, Greg has watched his daughters complete their education and grow into women. He rides in a powered wheelchair, and the front door of his house is powered also. Inside, tasteful decor is punctuated with eye-catching objects, retrieved from travels the family has made in Australia and other countries. Sharon prepares breakfast and lunch for him but he can eat meals unaided.

“Karen and I are fortunate that we’ve got the capital to live comfortably and we can travel,” says Greg, who invested in superannuation when he was working.

“And we get involved in things. We like the theatre. We love all varieties of music.”

He values Sharon for her willingness to help him participate.

‘We get involved in things. We like the theatre. We like all varieties of music.’

“I went out one evening with Karen and it was quite late that we returned,” Greg reports, offering an example. “Sharon made herself available to come out and provide a service. It was after midnight.

“When you have a disability, it seems sometimes that your life is programmed to a degree. Your independence is diminished somewhat. So having someone prepared to do something differently so that you have flexibility with your life – those support workers are exceptional.”

Sharon says of that episode: “I think that if they’re going to ask, they must need it. You’ve got to give someone a normal life. For a regular lunch shift or something like that, you’ve got to keep time. But in situations like a sleepover, or if you go away together, you want to have a normal life in that sort of time.”

Getaway

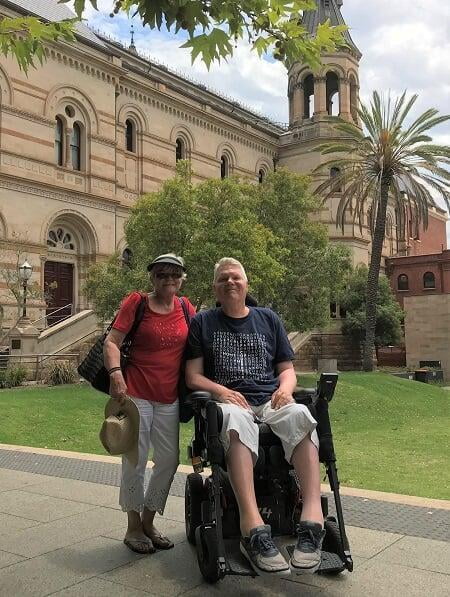

Greg says he is no longer strong enough for long trips overseas. So as Karen and his daughters planned a holiday last summer in the United States, he started planning to have a brief getaway.

“I thought, I don’t want to be here for a month when no one’s here,” Greg reveals. “I’d like to get away for a bit of different scenery. I’d been to every Australian State but South Australia.”

Sharon takes up the story: “Greg and his family had met my family at different times. I brought my mum one time because I had spoken about Greg so much and my mum said she would love to meet him, and Greg said, ‘Oh, bring her out one day.’ She’s not here any more – she died about 12 months ago. My family all came here to see my mum, so Greg’s met them all at one time or another.

“When Greg said he had never been to Adelaide, I said: ‘Oh, I’ve got a sister over there – we’ll be right. She’ll take us around and show us things.’ We went for about a week, and we had some fun. New Year’s Eve was a bit wild.”

‘I was still taking responsibility, but I was having a holiday. Greg didn’t expect me to work 24 hours a day.’

The two stayed at U City, a recently opened development that offers accessible serviced apartments in the centre of Adelaide.

“It’s a utopia in terms of technology, for people with disabilities,” Greg says of the short-stay accommodation, part of a project developed by South Australian non-profit Uniting Communities.

“It’s all sensors. You don’t have a light-switch – you just wave a card. The table went up and down, so that you could adjust it to the height of your chair. In the lift, you just waved your card and it knew which floor you were going to.”

Sharon says of the trip: “I was still taking responsibility, but I was having a holiday. Greg didn’t expect me to work 24 hours a day. Sometimes Greg would take off on his own for a few hours and give me a break.”

Careful washing, and gloves

Sharon’s primary means of resisting the transmission of COVID-19 has been to wash her hands carefully and often. She has made more use of gloves. She wipes down surfaces with disinfectants rather than ordinary detergents.

“I never put my hands near my face – and I don’t touch my hair with them,” she says.

No client has insisted that she wear a mask. She encourages clients to wear masks, however – mainly because she thinks it will help them feel confident. Most have accepted her guidance. [Editor’s note: this story was completed at a time when health authorities were not encouraging the use of face-masks in support settings.]

‘I never put my hands near my face – and I don’t touch my hair with them.’

Sharon was critical in late May 2020 of the State Government’s decision to relax social distancing measures, and said most of her clients agreed with her. The likelihood of a second wave of infections she believed to be high.

‘I just love it!’

Greg has other carers with whom he has worked for long periods. He considers himself an easy-going person who has been able to accept his circumstances. But he can understand that some people might be angry or embittered, and might express that in ways that discomfit those helping them. His own brother, he says, did not grapple with his illness very effectively.

“Neither you nor me would go to a workplace and be verbally abused,” he observes. “We wouldn’t tolerate it. So why should a support worker have to go into someone’s home where they’re verbally abused because of that person’s circumstances? I’ve had support workers tell me that they have felt quite fearful of going into some homes.”

Sharon responds with the suggestion that deeper training could help many support workers resolve difficulties of that kind. “If you had the training, you could work in with them,” she proposes. “A lot of support workers don’t have that training, and they just get scared and say, ‘I’m not going back there.'”

‘I’ve always loved nursing, and I’ve always loved being around people. And I’m loving this better.’

Sharon shares her house with her daughter and two teenage grandchildren. She works six days a week with a range of AQA clients, covering breakfast and lunch shifts with Greg.

She has been thinking about slowing down, but says she doesn’t want to retire.

“I’ve always loved nursing, and I’ve always loved being around people,” she says. “And I’m loving this better.

“It’s more exciting than just going to work and knowing that you’re going to be doing this every eight hours.

“I just love it.

“I get up, and I think: I wonder what’s going to happen today.”

- November 18, 2022