Story by Ian Baker

Geoff Dossetor lives and paints in south-eastern Melbourne in a thoughtfully renovated two-bedroom flat. His home has a living room that includes a bed, shower and kitchen, a second bedroom and bathroom, and a third room that serves as his studio. The second bedroom is reserved for Geoff’s young adult daughter, Taylor.

Geoff’s mum also lives in the complex. Another flat there houses Geoff’s support worker team: he rented it for them when the COVID-19 crisis arrived. Team members help him start work, by squeezing paint onto a palette.

Geoff paints from a powered wheelchair that has the capacity to raise him to a standing position. While it extends his ability to cover canvases, he also uses it hourly to relieve pressure areas. It is much better for him, he says, than an ordinary chair.

High flier Taylor was born at a time when Geoff had been, literally, soaring. Work as a relief teacher in Melbourne had supported a passion for hang gliding. An early instructor had identified him as a natural. He had taken his flying overseas, had won national championship events in New Zealand and Canada, and had taken a job flying tandem with intrepid tourists. He had purchased acreage in New Zealand near the tourist Mecca of Queenstown, and had set up a small but thriving business flying thrill seekers from nearby Coronet Peak to his personal landing ground. He had married his Canadian girlfriend, forming an instant family with her two girls.

“People say hang gliding is dangerous,” he says today, “but it wasn’t for me.”

By September 2001, when an awkward landing left him with complete C4-5 quadriplegia, Geoff had completed more than 5000 tandem flights. He believes his injury arose from a freak point of contact with his passenger, who was unhurt. Taylor’s birth had expanded the family to five: she was seven weeks old.

Geoff took on fully the raising of Taylor in 2007, at a time when, he believed, he

needed to take more responsibility for her. He had been living independently near the family property, with support funded by compulsory insurer the Accident Compensation Corporation. A court had awarded him permission to take Taylor to Melbourne, where his parents could help him look after her. He became one of very few people, he says, to reside outside New Zealand while receiving ACC funding.

Brought to earth

Geoff credits a moment from Taylor’s infancy with his electing to make the best of his circumstances. He had been strapped to his chair in the back of the family van, outside the lakeside hotel where he had been living, and Taylor, strapped into her child-capsule, had been crying.

In a moment of frustration, Geoff’s wife had walked away from the vehicle.

Geoff had said: “Would it be easier for everybody if I just went and rolled off the end of the jetty?”

“As I told her this,” Geoff recalls, “this crying baby, she just stopped crying and looked at me.

“And I took that as a sign that I had better stick around as long as I can.”

Soon after he returned to Australia with Taylor, Geoff joined AQA as a peer support volunteer.

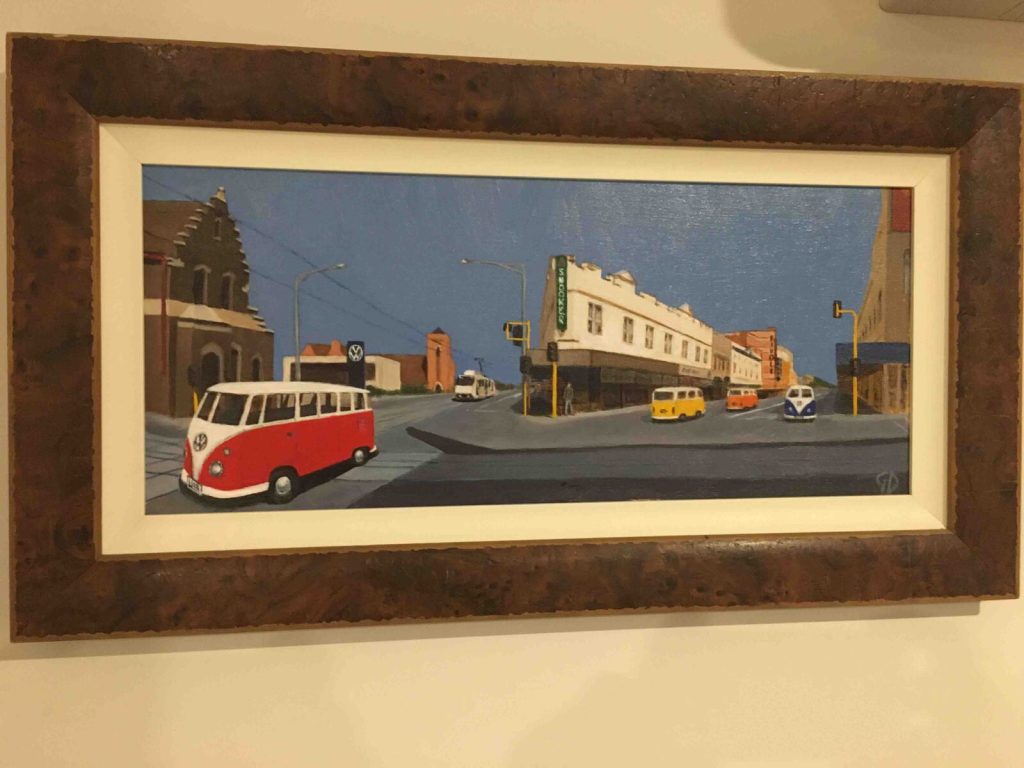

“I wanted to give back,” he says. “I had people help me in the early days. Some people don’t have a little sign that keeps them going.” Geoff took up painting during years after rehab that he spent in a nursing home. He doesn’t see himself as a natural artist, and he faults himself for laziness. He completes about a dozen paintings in some years, and fewer in others.

Keeping it real

Geoff receives an income for his art, in the form of a scholarship, renewed three-yearly, from the Association of Mouth and Foot Painting Artists (MFPA). The MFPA is an international organisation set up in the decades after the Second World War. The association raises money from card collections it mails to households at random, along with an invitation to make a voluntary payment.

Founder Erich Stegmann was adamant that the association support only people whose work stood up on its own, or that had the potential to do so. Geoff was awarded his scholarship in 2007, after submitting six paintings. He is one of only four living artists listed on the Association’s Australian website. He took Stegmann’s principle to painting classes he has attended online.

“I wanted to get realistic critiques,” he says, “Not somebody saying ‘Oh that’s good!’ – you know, for a mouth painting artist.”

He says it would be difficult in any case to find instruction that accounted for his capacity.

“Even among mouth painters, there’s different reasons why we’re mouth painters,” he observes. “Some people don’t have hands. They can’t pick up a brush. But they can walk up to an easel.

“I’m at the opposite extreme: I can’t do much at all. I need to be strapped into a chair. That’s one of the reasons I was able to get this kind of chair. I said: It will be good, because I’m able to raise it up and down, whether I’m seated or standing, to get to bigger canvases. That’s probably part of the reason I got funding for my first one of these, and this is now my third.”

- May 9, 2022