Story by Ian Baker

It is 85 years since an American film warned parents about the reefer madness that lay in wait for their children.

It is nearly 30 years since former US president Bill Clinton denied he had inhaled the marijuana that he admitted to trying.

And it is a little more than five years since the Access to Medical Cannabis Act 2016 passed in Victoria, making it the first Australian state to legalise therapeutic use of the controversial drug. Other states have followed.

In Victoria, any doctor may apply to prescribe cannabis for any condition. However, it is not likely that your local GP will do so, and for three main reasons.

First, almost no cannabis preparations have been registered as prescription drugs. Second, little is established about what ailments cannabis might help with, and how.

Third, a common ingredient of medicinal cannabis, THC, is classed as a Schedule 8 poison and a drug of addiction, like morphine, methadone and amphetamine. Therefore a doctor must seek authorisation before prescribing it for you, and may perceive the approval process to be very onerous.

Persistent pain

Nevertheless, a Senate inquiry was told early last year that more than 19,000 Australians had been prescribed medicinal cannabis, and there is evidence that the number has risen rapidly since.

One such Australian is former academic and state government policy adviser Ben Gruter, 65, who has been living with paraplegia from an incomplete T5 spinal cord injury since 2012.

When he resolved to try medicinal cannabis, Ben had spent seven years experimenting with other treatments for his persistent neuropathic pain, which arrived with his injury. He experiences the pain as located in his right leg, extending from his hip to his foot.

“It’s pain caused by damage to the nerves,” explains Ben, who is a peer mentor with the disability resource organisation AQA.

“It feels like the most intense pins and needles you’ve ever felt. Some people describe it as burning.

“It’s constant from the moment I wake up until the time I go to bed. Stress will make it worse; being relaxed makes it better.”

Surveys indicate that more than half of people living with spinal cord injury live with neuropathic pain.

Prior treatments

Ben spent 16 months in treatment and rehabilitation after his injury, which arose from a bleed in his spinal column. Initially he was given Panadol for his pain, and when he sought more relief he was prescribed an opioid, Oxynorm, and a pregabalin based anti-anxiety drug, Lyrica.

“By 12 months it was pretty clear that not only weren’t these drugs working, but I was having terrible side effects,” Ben reports.

Under the care of a pain team at the Austin Hospital, he tried alternative opioids, three anti-depressants, and ketamine, an anaesthetic. He says his pain remained very troubling, except when the ketamine put him to sleep.

‘Seeing Ben in pain has just been horrific. And the effects of a lot of the medication he was given have been awful.’

Subsequently, Ben was treated by a multidisciplinary team at the hospital’s outpatient pain clinic, finding some relief in hydrotherapy and in the cognitive behavioural therapy offered by the team’s psychologist.“Unfortunately they could only have me as a patient for six months,” he explains, “because it’s a high demand service.”

Marital conflict

When he was injured, Ben had been married for just four and a half years, to Christine.

“The partner or other family members of someone with a spinal cord injury are also severely affected by it,” Christine observes.

“I think for me, the worst of it has been Ben’s pain. Seeing him in pain has just been horrific.

“And the effects of a lot of the medication he was given have been awful.”

Memory loss is a recognised side-effect of pregabalin. Christine says conflicts arose at home from Ben’s memory lapses.

“We would have a specific conversation about something, and the next day Ben would deny that we even discussed it,” she reveals. “I actually just thought he was being difficult.”

I know a friend

Ben says he sought to reduce side-effects and cut his risk of addiction by decreasing his consumption of painkillers, in consultation with his GP.

For a few months he took no drugs at all. Today he takes no pregabalin and no Oxynorm, instead using an alternative opioid, tapentadol, in a slow-release formulation.

“When Ben did go off all the drugs, it wasn’t living,” Christine says.

“The pain is so consuming he just can’t do anything. He doesn’t want to go out. He doesn’t want to communicate with anyone. He can’t stand the grandkids coming in because they’re noisy.”

It was Christine who suggested to Ben that he might try cannabis. The topic had come up in conversation with a friend whose husband also had a spinal cord injury.

“My friend said it had been helpful,” Christine recalls. “And her husband said it was helpful.“So we met up and had a discussion, the four of us.”

Absolutely fantastic

“I’d seen the press reports,” says Ben, who like Christine had been exposed to the recreational use of cannabis when he was younger.

“Some medical practitioners said it’s very helpful. Other practitioners said it’s not helpful, and all the evidence isn’t in.

“I went into it with an open mind.”

About bedtime one evening, Ben used a dropper to administer himself a small dose of black-market cannabis oil, orally.

“For years I’d been sleeping about three hours each night before I woke up in pain,” he says of the result.

“That first night when I took cannabis, I slept for 10 hours.

“It was absolutely fantastic.

“I got a little high, and I got a dry throat. I didn’t get munchies.”

Christine adds: “And he woke up like a human, instead of a pain unit.”

Obtaining medicinal cannabis

About the beginning of 2019, Ben sought a prescription from his GP for medicinal cannabis. He says his doctor told him he would help, but then concluded that the approval and follow-up requirements would be too burdensome. Instead, the GP wrote a referral to the specialist clinic that had treated Ben’s acquaintance.

Medicinal cannabis typically comes in two forms, only one of which relies on THC – the component credited with producing euphoria. The active ingredient of the other form is CBD, which does not produce a high but is believed to have therapeutic value (some THC may be present).

After interviewing Ben and reviewing his history, the clinic prescribed him CBD, advising him to increase the dose each week until it was effective.

“When I wasn’t getting a good enough effect, they added THC,” Ben reports.

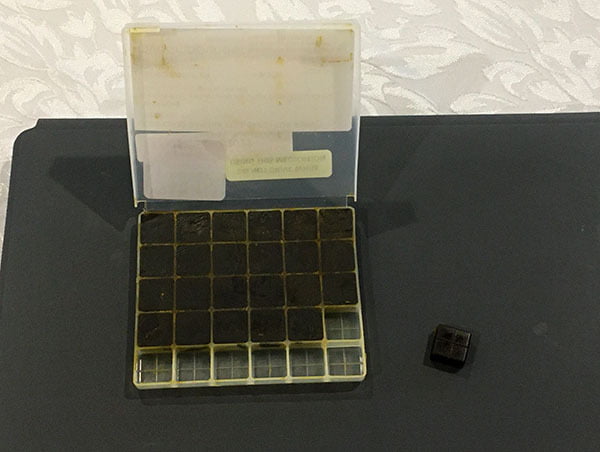

The cannabis comes from a Melbourne compounding pharmacy in tablet-sized resin lozenges, by registered mail. The lozenges are packed in small plastic containers that carry Ben’s prescription details. (The medication is available in other forms.)

He takes half a CBD lozenge orally, twice a day, and then a THC lozenge at bedtime.

“My understanding is that a typical joint is about 10 milligrams of THC,” Ben says, referring to the recreational user’s cannabis-infused cigarette. “I take 6.25 milligrams of THC. So this is probably a little bit more than half a joint.

“On the dose that I take, I don’t get high. If I was taking a lot more I would.

“It does make me drowsy – both the CBD and the THC make you drowsy. It tastes terrible. And I have a dry throat.

“I don’t know what would happen if I tried to really suppress the pain and take a lot more of it. I don’t want to try that, because I think I’d just fall asleep. So what’s the point of that.”

Hello Singapore

From Christine’s perspective, the therapy has been transformative.

“I would say within two or three weeks, Ben was engaging,” she says. “He was engaging with me, where he had been quite withdrawn before. He was engaging with the grandchildren. He was engaging with friends. We were going out. We were socialising.

“Within six weeks of him starting it, we had our first overseas holiday. Our first in seven years!”

The couple spent a week in Singapore, testing Ben’s capacity to make a flight twice as long to The Netherlands, where he was born.

“We had such a wonderful time. We were out every day. We couldn’t take the cannabis with us, but it took four days to wear off and then Ben still had his opioids.”

Prior to starting his cannabis therapy, Ben says, “I wouldn’t have dreamt of doing that trip.”

And he says the benefits have continued.

“The way I would describe it, is that it’s like the pain has been moved a bit away from you. So you’re not focused on the pain any more.

“The pain’s still there, perhaps level four rather than level six on a scale of 10, but it’s better. It’s not in your face.”

“And it’s not on his face,” Christine says. “He’s a lot more relaxed.”

A drug is a drug

Medicinal cannabis is not subsidised under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, and Ben’s prescription costs the couple about $500 a month. That’s significant for them, and they’re aware it would be out of reach for some people.

They would like to see medicinal cannabis become available more cheaply and more readily. Ben would also welcome changes to traffic law.

Driving under the influence of THC is illegal, and unlike alcohol no threshold is specified. “I’ve heard stories of people who won’t take THC because they’re afraid for their licence,” Ben says.

He adds: “I take a very, very small dose, and that’s also worth saying. It is possible that I will need a higher dose in the future. But I don’t need it now.

“And I’ve gotta say that although I’m a fan of cannabis – it’s probably the most benign of the drugs that I take for pain – it would be nice to get to a stage where I didn’t have any drugs, and could just rely on physiotherapy and psychological pain management systems.”

- July 1, 2021